Classical Diary: Moonlight Knight and Court Poet—Gilles Binchois (Part 4)

Classical Diary Series

[展开/折叠]-

How to Appreciate Classical Music — Written at the Very Beginning(Part1)

A brand-new column has been launched! Stay tuned for continuous updates in the future!

-

The Pope’s Dove and the Millennial Chant — Gregory I (Part 2)

Listen to the development of Gregorian chant and understand the characteristics of religious music

-

Budding Music, Hidden Epic — Guillaume Dufay (Part 3)

Listen to the story of the pioneers who laid the foundation for the fusion of technique and sensibility in the early Renaissance.

-

Moonlight Knight and Court Poet—Gilles Binchois (Part 4)

Listen to the delicate lyrical style of the Burgundian School, spanning millennia

In the history of European music, the dawn of the Renaissance is often overshadowed by the brilliance of Guillaume Dufay, yet without the gentle moonlight of Gilles Binchois (c. 1400–1460), this dawn would lose half its poetry. As the most delicate lyricist of the Burgundian School, Binchois subtly transformed the rigorous polyphony of the late Middle Ages into an art brimming with human warmth, in an almost secretive manner. He was not an international superstar like Dufay, who moved between popes and emperors, but rather a “musical poet” deeply rooted in the Burgundian court, using simple yet profound melodies to knock on the door of the Renaissance.

Overture: The Elegant Crucible of Power

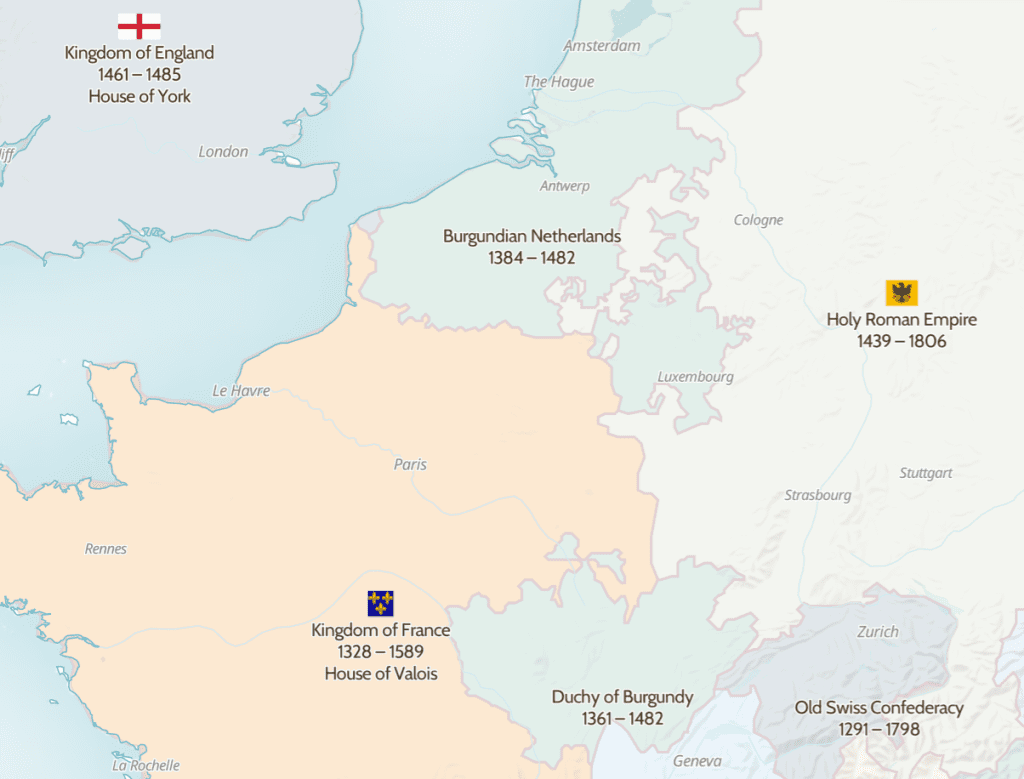

The Duchy of Burgundy in the 15th century was Europe’s greatest paradox: not a kingdom, yet it wove a web of wealth spanning the Low Countries and eastern France through marriage and diplomacy. At the court of “Philip the Good” (Philip III, 1396–1467), art was not merely decoration but a declaration of power. This duke, clad in gold-embroidered brocade, presided over Europe’s most extravagant court—maintaining a guard of two hundred knights and serving pastries shaped like peacocks and swans at banquets. Unlike the secular revelry of Italian city-states, Burgundian aesthetics blended the romance of chivalry with the solemnity of Christian piety—and music was the perfect vessel for this duality.

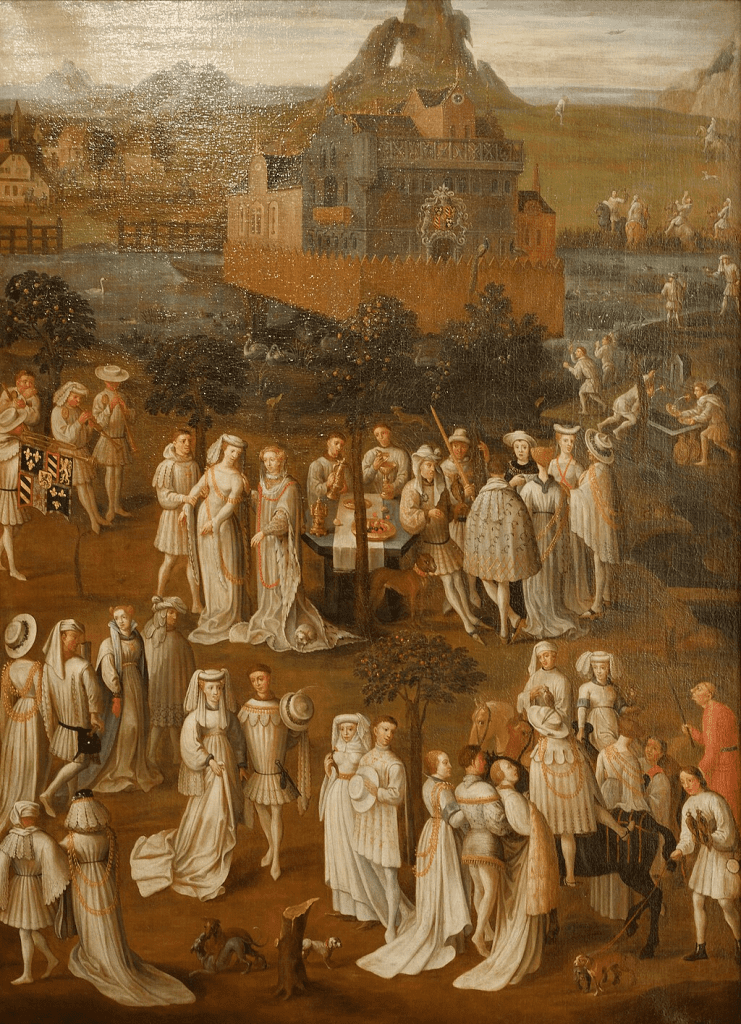

Cities like Dijon, Bruges, and Ghent—where the Burgundian court resided (the court had no fixed location)—lay at the crossroads of North-South European trade routes. They served as both commercial hubs for the Hanseatic League and outposts for Italian bankers venturing north. In 1430, Philip the Good married Isabella of Portugal (1397–1471), opening a cultural corridor between Burgundy and Iberia. At the wedding, Philip founded the famed Order of the Golden Fleece, an elite chivalric order whose members were nobles scattered across realms, collectively elevating knightly ceremonies to their zenith.

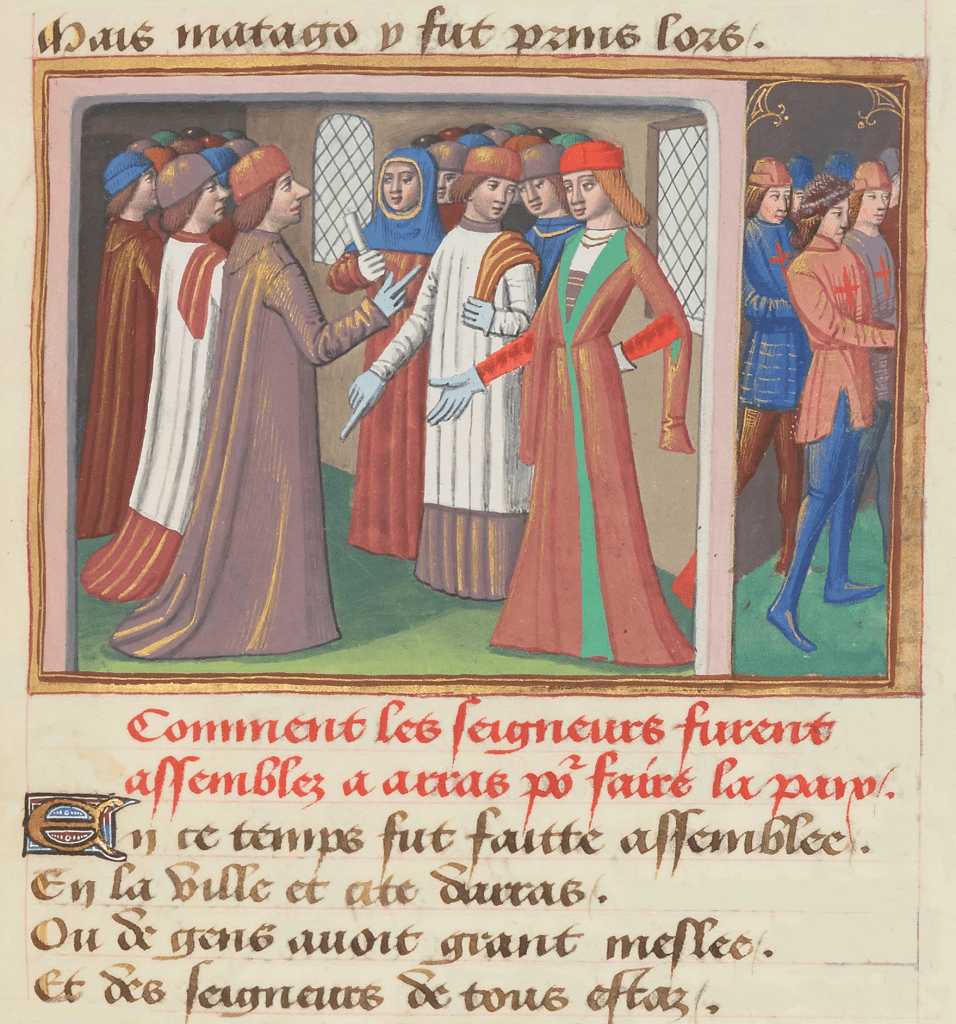

In 1435, Philip the Good successfully signed the Congress of Arras with King Charles VII of France, which ended the civil war between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, effectively forcing France to recognize Burgundy’s de facto independence. The growing political influence of Burgundy reflected the court’s deliberate cultivation of cultural soft power.

In the 15th century, while the Medici family was sponsoring painting in Florence, Duke Philip the Good was constructing another kind of Renaissance through music. Philip spent the equivalent of millions of euros today annually to support musicians. At its peak (around 1440–1450), his court chapel boasted 35 vocalists and 12 instrumentalists, a scale comparable to the papal chapels of Pope Eugene IV and Pope Nicholas V in Rome during the same era. As recorded by the renowned chronicler Georges Chastellain (c. 1405 or 1415–1475) in his monumental work *Chronique des faits et gestes de Philippe de Bonne, duc de Bourgogne*, the power of Burgundy was reflected in its cultural prestige and artistic patronage. Its court was a hall of civilization, not merely a source of warfare.

Movement I : The Musical Prodigy with a Gun

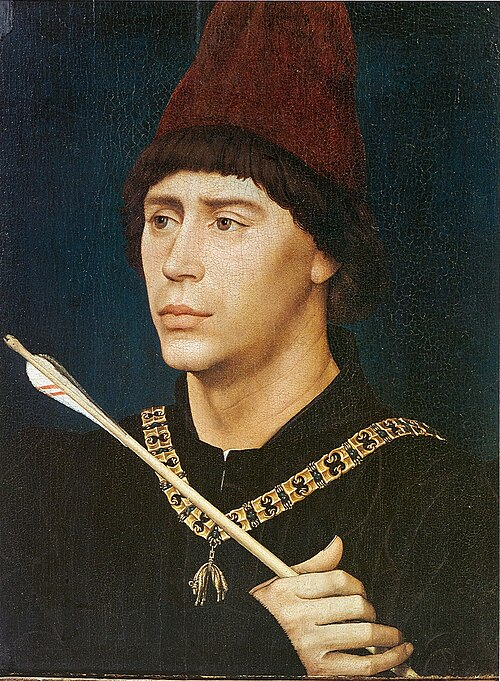

Guillaume de Binchois was born around 1400 in Mons, in present-day Belgium. His father, Jean de Binche, served as an advisor to William IV, Duke of Hainaut, and later to Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut, placing the family firmly within the “establishment.” Typically, children from such backgrounds were expected to pursue careers in government, but the young Binchois was determined to follow the path of art. Diligent and studious, he achieved considerable musical proficiency at a young age. In 1419, at just 19 years old, Binchois became the organist at the Church of Saint Waltrude in Mons. Being an organist in those days was a highly skilled profession. It involved not only the daily maintenance and repair of an instrument as large as the church itself but also the ability to showcase one’s virtuosity when superiors came to inspect. In his spare time, he was also expected to compose a few pieces and update the musical scores. Essentially, anything related to the organ fell under Binchois’s purview.

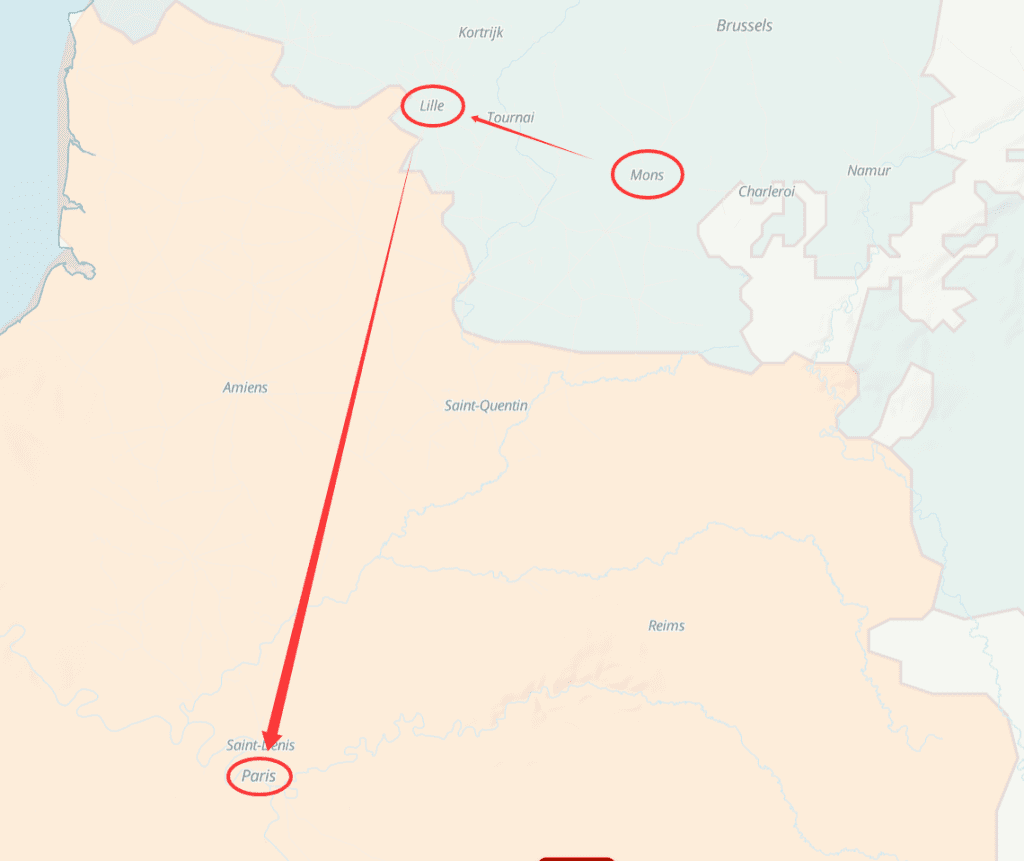

But Binchois was clearly not content with just playing the organ in the church. In 1423, as an art student, he suddenly went to Lille to join the army (historical records are scarce). At that time, the Hundred Years’ War between France and England was ongoing, and the Duchy of Burgundy was allied with England. There is evidence suggesting that Binchois may have served under William de la Pole, the Duke of Suffolk of England, and later followed the main forces to Paris.

It is now difficult to ascertain whether it was common practice in the Burgundian folk customs of the time for a church organist to suddenly take up a spear and go to war, but such an act—comparable to Beethoven picking up a rifle to join the Napoleonic Wars—seems somewhat abstract by today’s standards. A few years later, in 1426, the Duke of Suffolk commissioned Binchois to compose a little-known rondeau titled “Ainsi que a la foiz m’y souvient” (As I Sometimes Recall). Unfortunately, the original score has been lost, and only fragmented later copies remain, which may preserve part of the melodic framework.

Movement II : The Romantic Knight of the Court

Around 1427, Binchois officially joined the Burgundian court chapel, becoming a core court musician for Duke Philip the Good. As mentioned earlier, this duke was a true patron of culture, and his court ensemble was on par with the papal choir in scale. Records show that Binchois’s salary during this period was already 30 livres per year (roughly equivalent to the purchasing power of 150,000 euros today), giving a sense of how lavishly the Burgundian court was willing to spend. Binchois thrived in this environment, and in 1431, he composed the motet “Nove cantum melodie” for the baptism of the duke’s illegitimate son, Anthony (1421–1504)—a move that could be described as quite politically astute.

As time gradually passed, reaching the late 1430s, Binchois continued to study and create within the court. Together with his contemporary composer Guillaume Dufay (the protagonist of the previous article), he laid the foundation for the “Burgundian School.” The core characteristic of this style is reflected in its dominant three-voice structure: the high voice carries a clear and beautiful melody, the middle voice provides harmonic support, and the bass voice establishes a steady foundation and rhythmic framework. This simple yet balanced approach to voice handling intentionally abandoned the complex rhythmic techniques commonly found in medieval music, shifting toward a more direct and emotionally rich musical expression. This transformation in musical style is also widely regarded as one of the markers of the transition from the classical era to the Renaissance.

During the same period, Binchois was particularly renowned for his melodic innovations. His secular masterpiece “De plus en plus” exemplifies a highly mature three-voice Burgundian musical style through its fluid, song-like melodic lines and delicate emotional portrayal, perfectly aligning with Binchois’ creative state in the 1430s (believed to have been composed between 1430 and 1435). This piece has made it a quintessential 15th-century chanson.

Key Point: What is a “Motet-Chanson”?

[展开/折叠]-

Chanson Section: The upper voices (soprano and alto) perform a French secular lament poem. The lyrics are filled with accusations against death and mourning for the departed master Binchois, conveying sincere emotions—a hallmark of the typical “chanson” genre.The Motet Section: Meanwhile, the lowest voice part (the tenor) does not sing the French lyrics but rather a Latin chant text from the Requiem Mass, specifically the opening line: “Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine” (Lord, grant him eternal rest). This is a classic element of the motet.Thus, the hybrid name “Motet-Chanson” perfectly describes the unique structure of this work and reflects the exceptional skill of Renaissance composers.

Movement III: The Church’s Moonlight Poet

By the 1440s, Binchois had served at the Burgundian court for nearly two decades, with a stable position and at the peak of his creative output. During this period, his compositions gradually shifted from chansons to sacred music. Although Binchois’s greatest achievements in his lifetime were concentrated in his Burgundian chanson music, in reality, the majority of his surviving works are sacred compositions from the middle and later stages of his life. During this time, Binchois blended secular melodies with sacred texts, creating a large number of Masses and motets. His works were also copied and disseminated to places such as Italy and England.

A representative piece from this period is Binchois’s motet *Ave regina caelorum*, which showcases his fully mature polyphonic writing skills and his perfect mastery of the “Burgundian style.” It successfully blends the solemnity of sacred music with the elegant temperament unique to the Burgundian court, demonstrating his ability to transition effortlessly between sacred and secular themes.

Interestingly, in 1464, Guillaume Dufay also composed an extremely famous piece titled “Ave Regina Caelorum III,” which served as a personal prayer in preparation for his own death. Scholars generally believe that Dufay’s “Ave Regina Caelorum” was composed after Binchois’s work. Considering the possible exchanges between the two in their later years, it is likely that Dufay was aware of and drew inspiration from Binchois’s melody or creative concepts, then developed it into a larger and more personal composition. I encourage you, the audience, to listen to and compare the differences between these two pieces—it should be quite fascinating for understanding the creative philosophies of these two contemporary musical masters.

Movement IV : O, Brother Binchois!

Binchois officially retired from the Burgundian court in 1453 and settled in Soignies in the Hainaut region. This retirement was not merely a withdrawal from public life; he was granted a generous pension by the Duke of Burgundy and appointed as the dean of the collegiate church of Saint-Vincent—the highest recognition for his over thirty years of loyal service. In Soignies, although he was far from the lavish banquets of the court and the whirlpool of international politics, he did not withdraw from musical life. As the dean of the local church, he likely directed the musical activities of the choir and introduced Burgundian court music into local religious ceremonies.

September 20, 1460, Binchois passed away in Soignies and was laid to rest in the Church of Saint Vincent. His death sent shockwaves through the European music world, with the most profound tribute coming from his old friend Guillaume Dufay. Dufay composed the lament “O proles Hispaniae” in his honor, praising him in the lyrics as one “who filled the whole world with the sweetest melody” (qui totum orbem suavissima melodiae replevit). This praise was far from mere platitudes—it precisely captured the essence of Binchois’s art: using seemingly simple melodic lines to carry profound emotional resonance, allowing the boundary between the sacred and the secular to dissolve in music.

Final Movement: The Musical Prophet

Binchois’s historical status was swiftly established after his lifetime. Music theorist Johannes Tinctoris, in his 1477 work “De arte contrapuncti” (The Art of Counterpoint), ranked Binchois alongside Dufay and Dunstaple as “the most admirable composers of the fifteenth century,” emphasizing that their works “are still revered by the world today.” More importantly, Binchois’s melodic creations directly nurtured the next generation of Renaissance masters: Johannes Ockeghem inherited his long, song-like melodic thinking within polyphonic textures. Josquin des Prez further developed that ability to infuse delicate emotion into religious texts. Even into the 16th century, his works were still being copied, adapted, and used as creative material by musicians—this direct influence across generations confirms that Dufay’s praise of him as “filling the world” was no empty statement.

Afterword

Hello everyone, this is the BLOG owner of Dream Rain Lingyin. This is the first afterword for the Classical Diary series, and I can finally breathe a sigh of relief now that the early Renaissance chapter is complete. The Classical Diary series is something I’ve always wanted to write, but as the saying goes, the first step is always the hardest. In fact, many years ago, when this BLOG was first established, I had already started brainstorming and drafting related content. However, due to my limited writing skills, life experience, and appreciation level, I felt unable to produce works that would truly impress everyone, so I kept putting it off until now, when I’ve gradually started writing.

The entire Classical Diary is planned to start from the Middle Ages and progress all the way to the modern era, essentially guided by “figures,” accompanied by music, allowing everyone to read, listen, and reflect simultaneously. This is destined to be a lengthy writing project. In the past, just the translation alone would have overwhelmed the blogger, but now, with AI translation, researching materials has become much more convenient, saving the blogger a significant amount of time.

This lengthy article is destined to have few readers, but the blog author has still done their utmost to ensure the content is authentic and reliable. Much of the unverifiable information circulating on the internet has been diligently removed by the author, leaving only highly credible content. However, due to time constraints, the majority of the information comes from Wikipedia in various languages. For further verification of the original sources of musical scores or historical archives, the author can only consult scanned documents from digital archives for the most critical parts, unable to verify every single detail. Therefore, if there are any errors, the author sincerely hopes readers will leave comments to correct them.

Anyway, the blogger has mentioned more than once that this series is even more challenging than a graduation thesis. I hope these articles can lead more people to appreciate the charm of classical music and make a modest contribution to the Chinese internet. If this series is adapted into videos in the future, they will likely be uploaded to BILIBILI. Thank you once again! The next article should delve into the mid-Renaissance period!

References for this article

This text is translated from the original Chinese version on the author’s blog. For quoted content, please refer to the original article.