Classical Diary: Budding Music, Hidden Epic — Guillaume Dufay (Part 3)

Classical Diary Series

[展开/折叠]-

How to Appreciate Classical Music — Written at the Very Beginning(Part1)

A brand-new column has been launched! Stay tuned for continuous updates in the future!

-

The Pope’s Dove and the Millennial Chant — Gregory I (Part 2)

Listen to the development of Gregorian chant and understand the characteristics of religious music

-

Budding Music, Hidden Epic — Guillaume Dufay (Part 3)

Listen to the story of the pioneers who laid the foundation for the fusion of technique and sensibility in the early Renaissance.

-

Moonlight Knight and Court Poet—Gilles Binchois (Part 4)

Listen to the delicate lyrical style of the Burgundian School, spanning millennia

Finally, we have left behind the ignorant Middle Ages and entered the most splendid period in the history of human art—the Renaissance, an era when the European continent was slowly awakening. Today, this blog will primarily recount a hidden yet magnificent epic—the revival of early Renaissance music. This is a legend about how power, wealth, war, and peace gave birth to a new sound. Its protagonist is not a solitary artist but a musical prophet who moved among royal courts, churches, and city-states.

Overture: Echoes of the Old World and the Dawn of a New Order

The 14th century in Europe was a long, harsh winter. The shadow of the Black Death had not yet lifted, and the Western Schism (1378–1417) saw rival popes in Rome and Avignon, tearing a rift in sacred authority and plunging the spiritual world into confusion and doubt. In music, the French-born *Ars Nova* (New Art) style was at its peak, characterized by complex rhythms, intricate notation, and highly intellectualized isorhythmic motets. This music was the plaything of scholars and theologians—complex and abstract, like the carvings atop Gothic cathedrals, barely visible to ordinary mortals.

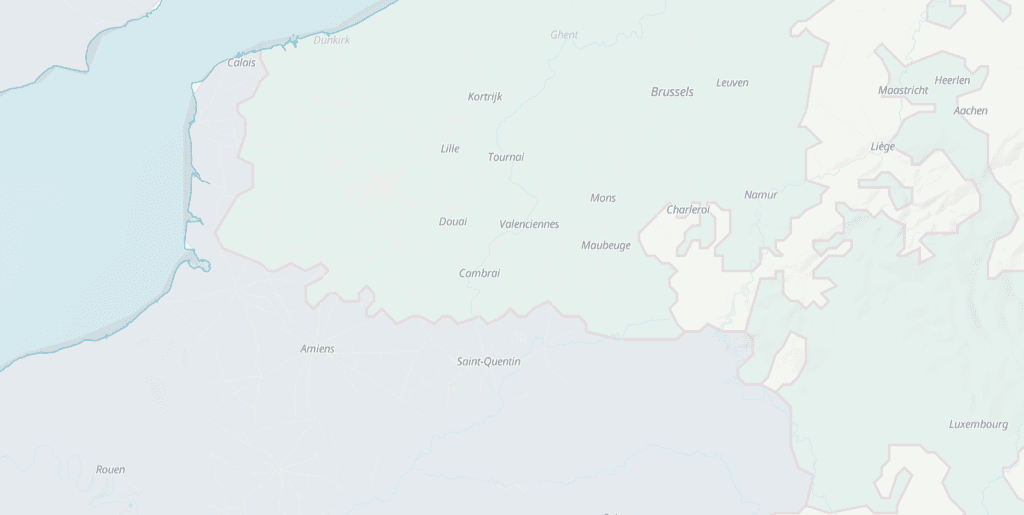

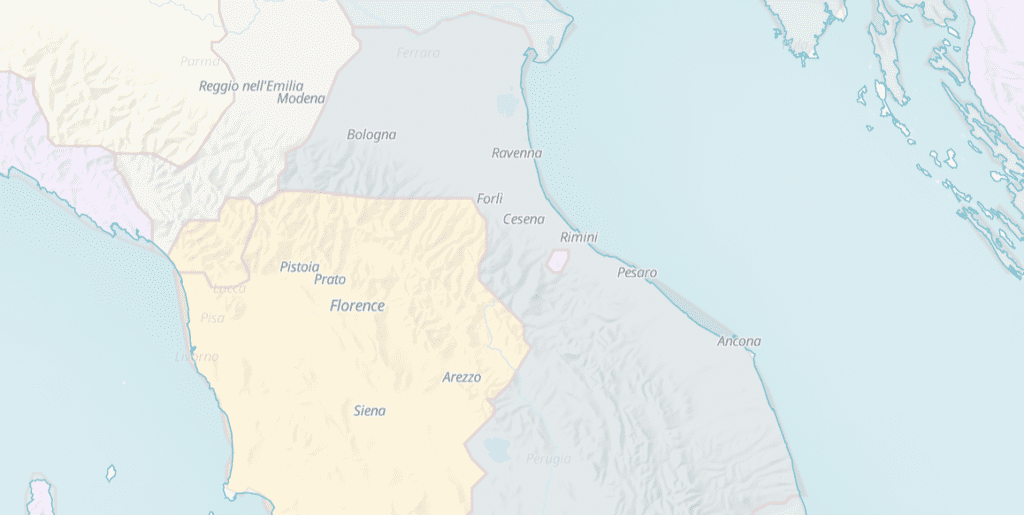

Yet, beneath this seemingly frozen soil, new seeds were sprouting. In Italian cities like Florence and Venice, merchants and bankers amassed unprecedented wealth, fostering a new secular culture and a growing fascination with classical humanism. In the north, the Duchy of Burgundy was staging a political miracle. Not a vast empire, but a “patchwork kingdom” woven through a series of marriages and shrewd diplomacy, it encompassed the wealthy regions of present-day northeastern France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

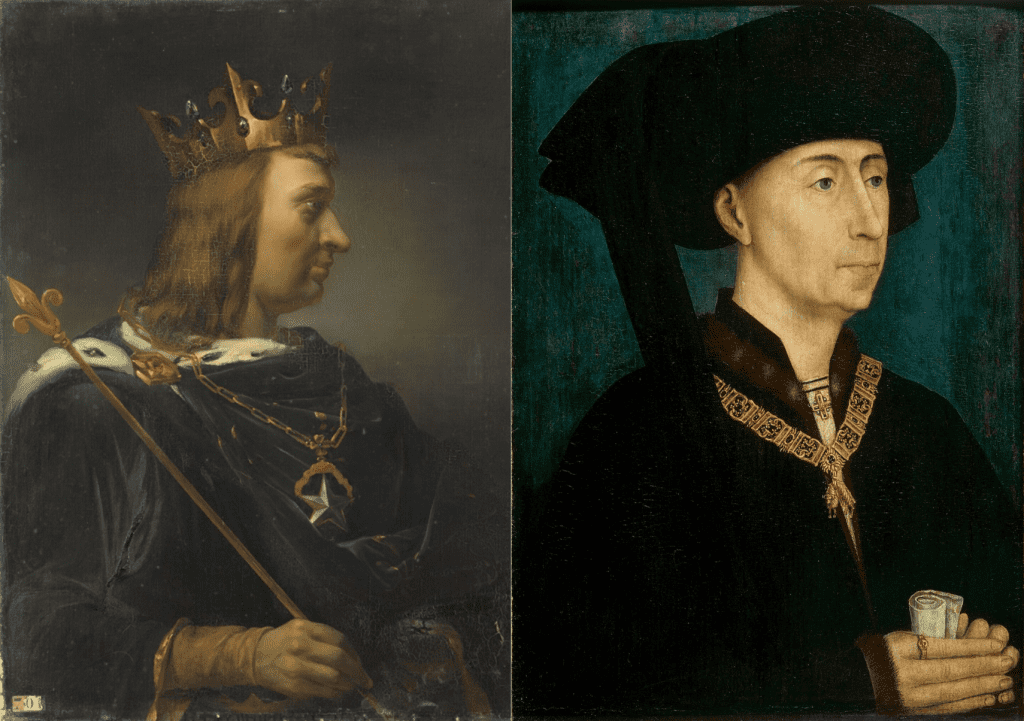

Under the rule of four successive dukes—John the Good (John II, 1319–1364), Philip the Bold (Philip II, 1342–1404), John the Fearless (John I, 1371–1419), and Philip the Good (Philip III, 1396–1467)—the Burgundian court became Europe’s most dazzling cultural center. Eager to showcase their power and prestige through the splendor of art and music, they sought to outshine their nominal overlord, the King of France. Unburdened by the heavy theological baggage of the papacy, the court embraced a refined, elegant, and pleasure-seeking “courtly chivalric spirit.” Music moved from the church altar to the palace hall, shifting from abstract mathematical exercises toward serving the expression of concrete emotion.

In the chronicles of the Burgundian court, the names of musicians began to appear alongside those of dukes, knights, and diplomats. Among them, two of the brightest stars were Guillaume DuFay and Gilles Binchois. One was like the sun (DuFay), radiant and grand in structure; the other like the moon (Binchois), gentle, serene, and deeply moving. Their collaboration and rivalry defined the trajectory of early Renaissance music. Today, we focus on one of them, Guillaume DuFay, to understand this musical giant, a prophet of the Renaissance, savor his compositions, and glimpse into his life.

Movement I : The Crossroads of Music (1397-1430)

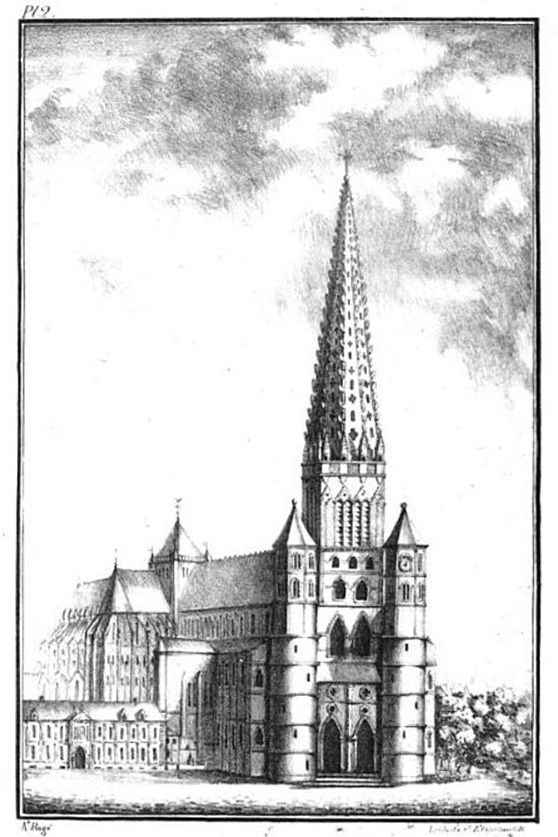

Du Fay’s life itself is a map of early Renaissance Europe. He was born in Cambrai (now in northern France, then part of Burgundian Netherlands), spent many years traveling through Bologna, Rome, Savoy, and other places in Italy, and returned to his homeland in his later years with great honor. He served the Pope and also worked for secular monarchs. This rich experience allowed his music to blend the polyphonic techniques of the North with the melodic beauty of Italy.

Key Point: What is “Polyphony”?

[展开/折叠]-

Imagine the simplest form of music: a person singing “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” a cappella. This is called monophonic music, with just a single melodic line—simple and straightforward.

Now, let’s try something more complex: you sing “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” I sing “Frère Jacques” at the same time. Another person hums a completely different melody simultaneously. If we just sing chaotically like that, it would definitely be noise and unbearable to listen to.

But if a genius composer carefully designs these three melodies so that, although each is independent and completely different, when combined, their pitches and rhythms fit together perfectly, sounding exceptionally rich, magnificent, and harmonious—this is called “polyphonic music.”

Let’s turn the clock back to 1397, around the time when our Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty was rolling up his sleeves to embark on his grand endeavors. In a place called Cambrai or perhaps some nearby villages in Europe, our protagonist, little Du Fay, was born. Cambrai was no impoverished countryside—it was a cultural crossroads in northern France, where various arts converged and blended. From a young age, little Du Fay displayed the standard talents of “someone else’s child”—a beautiful voice, a sharp mind, and in the church choir, he was practically the center of attention from the start. Even God would have been tempted to tap His feet to his singing.

However, becoming a local internet-famous singer was clearly not Dufay’s goal. In 1417-1418, at the age of 20, Dufay, as an outstanding performer, accompanied the Bishop of Cambrai to the Council of Constance (1414-1418). This council gathered nobles and elites from across Europe, accepted the resignation of Pope Gregory XII, deposed two rival popes, and elected Pope Martin V, ending the Western Schism—a major event in European history. On such a grand stage, Dufay’s performance was nothing short of stunning. His exceptional singing skills caught the attention of Carlo I Malatesta. Consequently, starting in 1419, he was invited to Rimini to serve at the court of the Malatesta family.

Carlo Malatesta was a renowned condottiero and humanist who, along with Pandolfo III Malatesta (his father), the head of the Malatesta family at the time, held high regard for the exceptionally talented young Dufay. Under their (patrons’) influence and support, the young Dufay was not only able to further his musical education but also immersed himself in the humanist ideals of the early Renaissance. This exposure led him into the Burgundian cultural circle, paving the way for his future creative endeavors.

In the following years (1420-1430), Dufay worked under Cardinal Louis Aleman, the papal legate, and continued to showcase his astonishing musical talent. During this period, he traveled tirelessly across Italy, serving in the courts and churches of various city-states such as Pesaro, Bologna, and Rome. At this time, he was exposed to the smooth, melodious secular music style of Italy, which was entirely different from the complex polyphony of the North he had previously studied. During this period, Dufay’s representative work was a chanson titled *Adieu ces bons vins* (Farewell to These Fine Wines), expressing his homesickness. (Chansons, masses, and motets were the three most common musical genres of the time.)

Key Point: What is a “Motet-Chanson”?

[展开/折叠]-

Chanson Section: The upper voices (soprano and alto) perform a French secular lament poem. The lyrics are filled with accusations against death and mourning for the departed master Binchois, conveying sincere emotions—a hallmark of the typical “chanson” genre.The Motet Section: Meanwhile, the lowest voice part (the tenor) does not sing the French lyrics but rather a Latin chant text from the Requiem Mass, specifically the opening line: “Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine” (Lord, grant him eternal rest). This is a classic element of the motet.Thus, the hybrid name “Motet-Chanson” perfectly describes the unique structure of this work and reflects the exceptional skill of Renaissance composers.

Movement II: The Origin of the Renaissance (1430–1439)

Around 1427–1428, Dufay was formally recruited into the Papal Choir in Rome due to his exceptional artistic talent. In the same year, he was ordained as a priest in Bologna. However, just as Dufay was preparing to make his mark, his greatest patron, Cardinal Aleman, was expelled from Bologna by the local power, the Canedoli family. “When the boss gets laid off, the underlings suffer too.” Dufay had no choice but to follow his patron, leaving everything behind and heading to Rome to seek new employment.

In 1433, coinciding with the meeting between Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III and Pope Eugene IV in Rome, Dufay composed his representative work of this period, “Supremum est mortalibus bonum” (The Highest Good for Mortals), to celebrate this great occasion, highlighting the significant role of music in political diplomacy.

In the first half of 1434, Dufay had just been appointed as the court chapel master for Duke Amadeus VIII of Savoy. In June, the conflict between the Catholic Church and the Council of Florence (1431–1445) intensified, and Pope Eugene IV was forced to flee Rome due to a rebellion. Dufay, who was part of the papal choir in Rome, was inevitably caught up in the turmoil. With his employer forced to flee, he had no choice but to leave Rome as well. In 1435, Eugene IV went into exile in Florence and reestablished the papal court there. Once everything settled down, the Pope, sitting in his temporary office, slapped his thigh and exclaimed, “Bring Dufay to me at once! How can the papal court be proper without sacred chant?” Thus, Dufay quickly ended his period of unemployment and resumed his service in the papal chapel.

Over a decade of experiences, moving through multiple cities, allowed Dufay to masterfully blend the rigorous, complex Gothic cathedral polyphony of the Franco-Burgundian tradition with the newly encountered sweet, flowing melodies of the Italian style. This culminated in a “complete fusion from technique to concept,” forming his unique musical creative style. In 1436, after 18 years of traveling abroad, Dufay (then 39 years old) composed his most celebrated work in Florence for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore—the festive motet “Nuper rosarum flores” (The difference between a motet and a mass can be likened to that between a single and a suite). This piece not only showcased his exceptional compositional skill but also demonstrated his ability to perfectly combine complex counterpoint (technique) with moving melodies (emotion), making it one of the most important and representative works of early Renaissance music.

This motet was composed for the consecration ceremony of the dome of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, presided over by Pope Eugene IV in exile. Undoubtedly, the Pope greatly praised this piece, “Nuper rosarum flores.” The following year, the Pope personally awarded him an honorary degree in canon law, a significant achievement that was engraved on Dufay’s tombstone before his death, marking the pinnacle of his life. Around the same time, Dufay also connected with one of the most important patrons of music during the Renaissance, the Este family of Ferrara. With substantial financial support, Dufay finally achieved financial freedom (or at least creative freedom), which played a crucial role in ensuring the preservation and legacy of his compositions.

Movement III : The Pioneer of Cantus Firmus Mass (1439–1458)

However, the struggle between the papacy and secular powers proved to be brutal. In 1439, after intense conflict, Eugene IV was ultimately deposed by the Council, and Amadeus, Duke of Savoy, proclaimed himself the antipope Felix V (also known as Amadeus VIII, serving as pope from 1439 to 1449). Sensing the crisis, Dufay believed that survival was paramount (in fact, Dufay had a decent relationship with Felix V). Thus, in December of the same year, Dufay hastily left the center of papal power and returned to his hometown of Cambrai, where he took charge of instructing the boys’ choir and the cathedral choir. Over the next decade, Dufay focused on self-cultivation, rarely venturing far from his hometown. During his time in Cambrai, he collaborated with Nicolas Grenon (an early Renaissance French composer) to comprehensively revise the cathedral’s liturgical music collection, which included composing numerous polyphonic works for religious ceremonies. In addition to his musical endeavors, he actively participated in the daily administrative affairs of the cathedral.

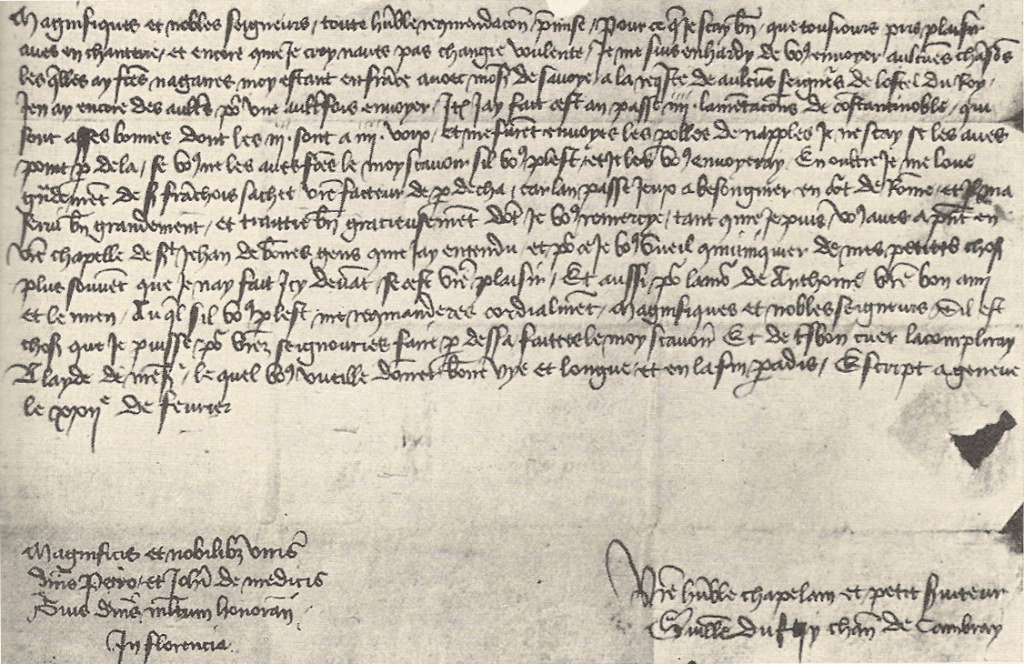

In 1449, after the abdication of Felix V, the power of the Duke of Savoy collapsed, and the factional struggles within the Church gradually subsided. Dufay once again left Cambrai and headed south. In 1452, he set out for Savoy, where he spent six years. During this period, Dufay not only continued his compositions but also maintained connections with many prominent families and figures, including correspondence with Lorenzo de’ Medici.

During his time in Savoy, Dufay, much like modern doujin music creators, began composing a type of music known as the “cantus firmus mass.” In simple terms, this involved taking popular chansons, setting them to the same melody, and adapting them into mass settings. This sophisticated yet accessible, lyrical yet solemn form of composition spanned the entire Renaissance period, significantly elevating the artistic status of secular music and becoming a crucial component of 15th-century musical development. As the pioneer of this genre, his representative work, *Missa Se la face ay pale*, uses the melody from his own hit single—a love song titled *Se la face ay pale*—as its core, enriched with the solemnity of the mass. This is one of the earliest and most famous cantus firmus masses in the world, but more importantly, it holds landmark significance not only for its technical innovation but also for its cultural symbolism. It marks the formal, systematic fusion of a secular melody (a love song about romance) with a sacred text (the mass). This perfectly embodies the blurring of boundaries between the sacred and the secular during the Renaissance, as well as the influence of humanist spirit on the arts. (The sample provided is only the first movement; for the full version, please click to jump.)

The original chanson *Se la face ay pale* (If My Face Is Pale), composed around 1430.

The cantus firmus mass *Missa Se la face ay pale*, composed around 1450.

Key Point: What is “Missa” (Mass)?

[展开/折叠]-

In music, “Missa” (Mass) is a large-scale religious vocal suite, where composers set music to several fixed and most important texts of the Catholic Mass liturgy. A complete Mass typically consists of the following five core sections (movements):

Kyrie (Kyrie Eleison): A plea for God’s mercy.

Gloria (Gloria in Excelsis Deo): Praise for the glory of God.

Credo (Credo in Unum Deum): A declaration of faith.

Sanctus / Benedictus (Sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth / Benedictus qui venit): Acclamation of God’s holiness.

Agnus Dei (Lamb of God): Praying for the Lamb of God to take away the sins of the world.On CDs or streaming playlists, each movement is typically treated as a separate track for the convenience of listeners.

Key Point: What is “Cantus Firmus”?

[展开/折叠]-

During the Renaissance, when composers created Mass settings, a technique known as “Cantus Firmus” was highly popular. They would borrow an existing melody (which could be from a chant or a secular song) and, much like laying the foundation for a building, use this melody as a base, weaving other new and complex voices above and below it.This is somewhat akin to the modern practice of fan music rearrangements and reinterpretations. The most classic example is Touhou fan music, where the same melody is rearranged by different circles or individuals. During the era of the cantus firmus, several composers used the same melodic line as a foundation to create their own versions of the Mass, showcasing and competing with their compositional skills—a uniquely romantic artistic endeavor.

Movement IV : Passing the Torch (1458-1474)

In 1458, at the age of 61, Dufay accepted a senior ecclesiastical position (canon) at the Cathedral of Cambrai, officially entering a semi-retired state. By this time, he was already the most renowned composer in Europe, enjoying a lofty status with ample wealth and few responsibilities. Between 1451 and 1460, Dufay composed the *Requiem Mass* for the death of Duke Amadeus VIII of Savoy (Felix V), one of the earliest surviving polyphonic requiem masses, though unfortunately only fragments of the manuscript remain today. In 1472, Dufay created the motet *Missa Ave regina celorum*. He incorporated the melody of a hymn (Antiphon) dedicated to the Virgin Mary into the mass and inserted a prayer for himself and his patrons at the end of the *Agnus Dei*, imbuing the work with profound personal character and emotional depth, making it a crowning achievement of his later years.

In his later years, Dufay received numerous visitors, including Antoine Busnois, Johannes Tinctoris, and Loyset Compère—all musicians who played decisive roles in shaping the development of the next generation of polyphonic styles, each influenced to varying degrees by Dufay. However, the most significant figure among them was likely Johannes Ockeghem, the leader of the next generation of the Franco-Flemish school and arguably Dufay’s legitimate successor. Dufay’s late works, particularly the *Missa Ave regina celorum*, directly influenced Ockeghem’s compositions in terms of the complexity of polyphonic techniques and emotional depth. The dense, elongated melodic lines in Ockeghem’s masses can be seen as both an inheritance and an evolution of Dufay’s late style.

In November 1474, Dufay fell seriously ill. According to his own request, he wished for people to sing his “Ave Regina Caelorum” before his passing, with passages pleading for mercy inserted between the verses of the hymn. However, due to the sudden onset of his illness, on November 27, 1474, the 77-year-old Dufay passed away in Cambrai. Ultimately, he did not live to hear his own Mass and was buried in the Chapel of Saint-Étienne in Cambrai Cathedral. His tombstone was discovered in 1859 and is now preserved in the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille.

Final Movement: Knocking on the Door of the Renaissance

In Europe before the 15th century, the modern concept of a “composer” had not yet emerged. Musicians primarily existed as performers or improvisers. It was not until the 15th century that the scales of history began to tip, and a new professional identity gradually took shape—the musician who regarded creation, rather than interpretation, as their core mission stepped onto the stage.

And Dufay and Binchois, in that era, jointly defined the musical development history of the early Renaissance. The two of them were respectively the musical leaders of the two most important cultural centers of the time: Dufay’s sphere of activity was more international (Italy, Savoy, Cambrai), while Binchois served stably and long-term at the court of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and was a central figure in Burgundian music. Although they belonged to different “units,” they seemed to stand at the intersection of two eras, embodying a grand spirit that both inherited the past and ushered in the future.

Dufay was the last master to profoundly grasp and apply the essence of late medieval polyphony, under whose hands the complex and intricate “isorhythm” technique reached its final brilliance; at the same time, he was also among the earliest prophets to embrace the dawn of the Renaissance, infusing music with new vitality through more humanistic, flowing melodies, clear harmonies, and balanced phrases.

Dufay’s greatness does not stem from the breadth of his subject matter, but from his extreme refinement of form. Whether in grand masses, intricate motets, or elegant chansons, he endowed them all with a unified and sublime artistic character through an almost perfect mastery. His reputation rests on a broad consensus among his contemporaries and successors: his grasp of musical form reached a state of perfection, and the melodies that flowed from his pen possess both an unforgettable, timeless charm and a natural, elegant fit for the human voice.

Since the dawn of the Renaissance illuminated the fifteenth century, he has been widely recognized as the most outstanding composer of his era. This acclaim has traversed centuries, and its brilliance continues to shine undimmed in the hall of a thousand years of music history.

References for this article

This text is translated from the original Chinese version on the author’s blog. For quoted content, please refer to the original article.