Classical Diary: The Pope’s Dove and the Millennial Chant — Gregory I (Part 2)

Classical Diary Series

[展开/折叠]-

How to Appreciate Classical Music — Written at the Very Beginning(Part1)

A brand-new column has been launched! Stay tuned for continuous updates in the future!

-

The Pope’s Dove and the Millennial Chant — Gregory I (Part 2)

Listen to the development of Gregorian chant and understand the characteristics of religious music

-

Budding Music, Hidden Epic — Guillaume Dufay (Part 3)

Listen to the story of the pioneers who laid the foundation for the fusion of technique and sensibility in the early Renaissance.

-

Moonlight Knight and Court Poet—Gilles Binchois (Part 4)

Listen to the delicate lyrical style of the Burgundian School, spanning millennia

We’ve finally arrived at the main feature of the Classical Diary series. Unlike the previous installment, starting from this entry, the BLOG author will focus on major historical events and significant figures. You can treat it as a story to explore the trajectory of music’s development. The BLOG author will attempt to offer a unique perspective, delivering a more intuitive, emotional, and engaging lecture on classical music appreciation.

Today, we’re going to discuss a story that lasted an entire millennium. Its protagonist is a melody you’ve likely heard in the background music of *Harry Potter* or *Game of Thrones* but probably couldn’t name. Its inventor (or at least its namesake) was a pope whose fate was changed by a dove. This is the most hardcore cultural legacy in medieval music history—Gregorian Chant—and its “spokesperson,” Pope Gregory I.

Don’t think this thing sounds like background music in a fancy café now, but over a thousand years ago, the Church’s sacred chants were the TOP1 “hit chart” across the entire European continent, mainly because everything after TOP2 was wiped out, so it reluctantly dominated the charts for centuries. However, all things rise and fall in the river of time, and even the mighty Church nearly turned these chants into history! Their fate is closely tied to the collapse of the Roman Empire, the rise of papal power, the expansion of the Frankish Empire, and even a legendary singing pigeon.

Movement I: The Empire’s Sorrow—The Era of a Hundred Schools of Sacred Song Contending

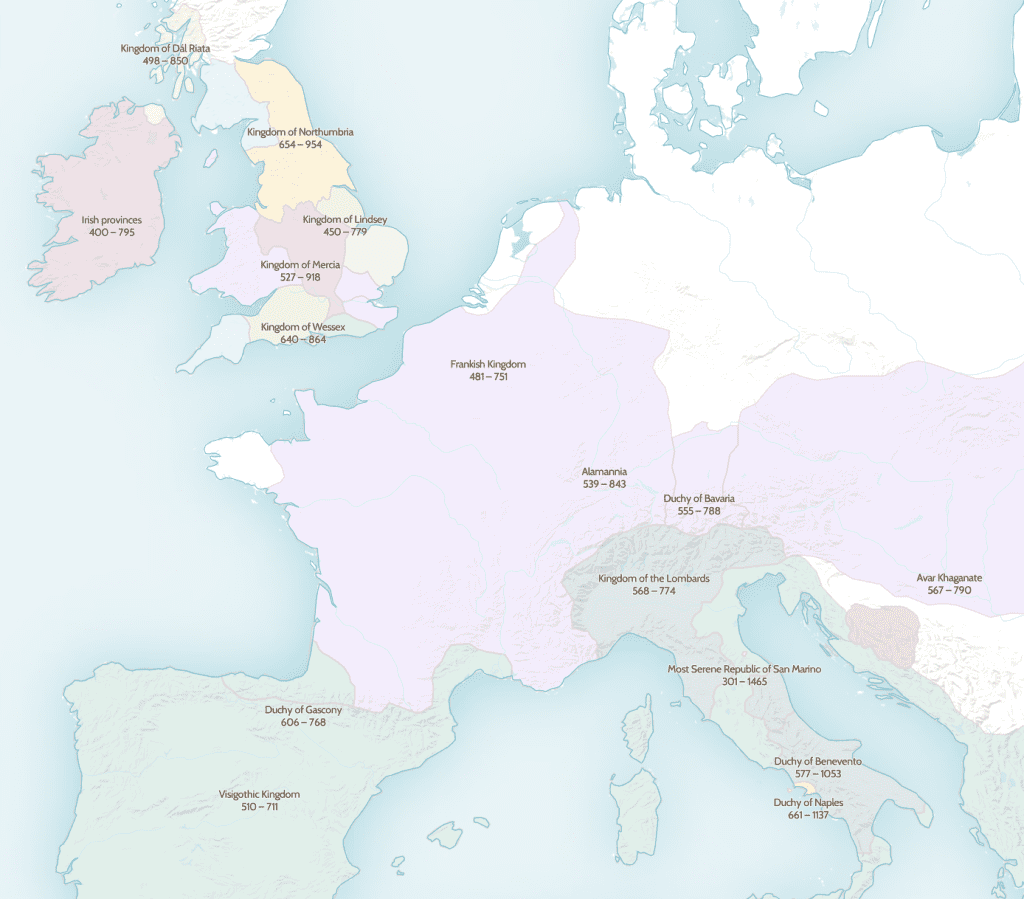

In 476 AD, Romulus Augustulus, the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire, was kicked off the throne by Odoacer, the Germanic mercenary leader. This kick didn’t just oust an emperor; it effectively shut down the entire European server, akin to deleting the operating system and leaving it open to install whatever came next.

Over the next few centuries, the entire European continent descended into a state of chaos and conflict. The only institution that continued to strive to maintain order was likely the Catholic Church, this “time-honored establishment.” Music, as a fundamental human need for emotional expression, naturally did not disappear. However, in this “apocalyptic atmosphere,” with poor communication and diverse cultures, churches in different regions began to develop their own distinctive characteristics. Even the originally rigid and complex chants flourished and diversified.

1、Old Roman Chant

In the long early Middle Ages, a unique kind of singing echoed through the churches of Rome—this is what we now call “Old Roman chant,” the liturgical songs of the time. It was not merely a medium for prayer but a flowing history, a story of power, dissemination, and oblivion.

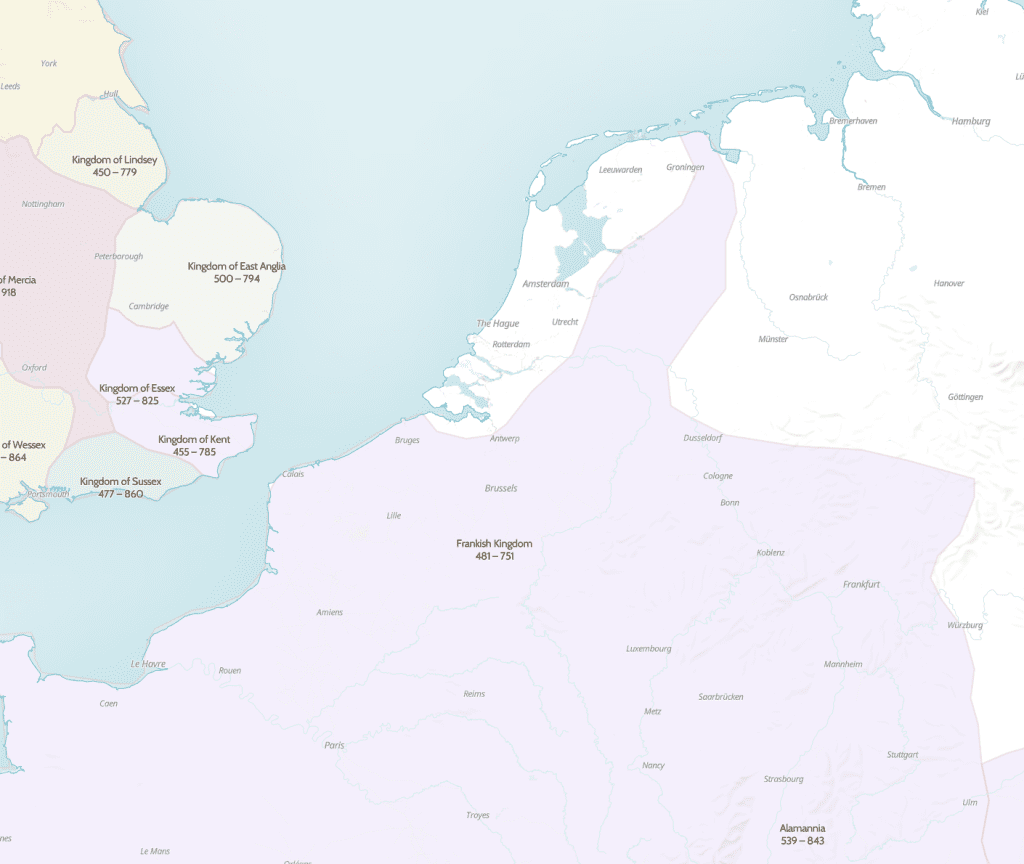

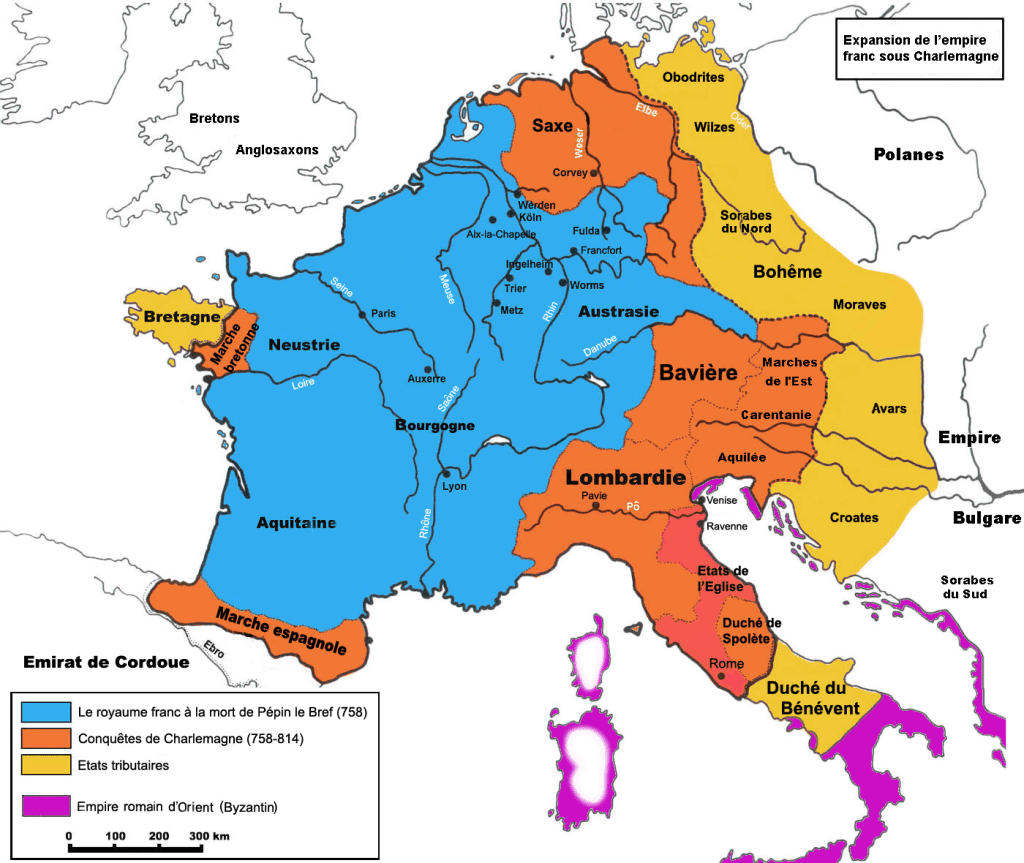

In fact, the relationship between Old Roman chant and the later unified chant form known as “Gregorian chant” is the closest. The two share the vast majority of liturgical texts, and even many melodies are highly similar, as if originating from the same source. A widely accepted explanation relates to power. Around 750 AD, the Carolingian dynasty of the Franks—particularly Pepin III and Charlemagne—actively introduced a set of chants from Rome to consolidate their rule and strengthen ties with the papacy. This ancient melody did not remain unchanged as it traveled north. On Frankish soil, it absorbed characteristics of the local Gallican chant, gradually evolving into what we now know as “Gregorian chant.” While it was evolving in the north, the chant that remained in Rome itself developed independently, forming a more ornate and complex style known as “Old Roman chant.” There is also a more obscure legend suggesting that Rome itself had “two singing traditions” at the time: one used for the solemn liturgies of the Vatican pope, which was taken north, and another used in the various churches within Rome, which remained locally. This may explain why the two, though sharing the same origin, ultimately diverged.

The historical turning point occurred between the 11th and 13th centuries. With the political power of the Carolingian dynasty and the extensive network of the Benedictine order, Gregorian chant “flowed back” from the north and gradually replaced its Roman counterpart. Rome even developed a tradition of introducing chant from the German emperors. Thus, the ancient melodies that once echoed over the Seven Hills gradually fell silent and were eventually completely forgotten. Gregorian chant, in a reversal of roles, was later mistakenly regarded by posterity as the “authentic” Roman chant—a beautiful misconception that persists to this day. Fortunately, we have not entirely lost the ancient Roman chant. It lies preserved in a handful of surviving manuscripts—primarily three *Graduals* and two *Antiphonaries* copied between 1071 and 1250. Through these precious documents, we can faintly hear its former splendor. What we can listen to today, such as the album *Chants de l’Église de Rome* released by the ensemble “Organum,” offers a glimpse into this later reconstructed tradition of ancient, rustic Roman chant.

2、Celtic Chant

In the 5th century, after the fall of the Roman Empire, the European continent was thrown into chaos. However, the remote regions of Ireland and Britain, situated at the edge of the world, remained largely unaffected. Instead, a group of unconventional monks emerged there—they lived in stone monasteries by the sea, copying scriptures and praying daily amidst fierce winds and towering waves, and incidentally developed their own liturgical system: the Celtic Rite. Theoretically, they acknowledged the Pope in Rome as their leader, but in practice, the Pope’s decrees took so long to reach Ireland that by the time they arrived, the great-grandsons of the local monks might already have become bishops. As a result, the development of chant in the Celtic Church followed a path of “self-reliance.” Yet, precisely because of this, when Pope Gregory I later unified the world of chant, Celtic chant was targeted most severely. Ultimately, almost no musical scores of Celtic chant have survived—after all, the monks of that time preferred oral transmission, considering notation unnecessary. The only piece that may have preserved some traces of Celtic chant is the hymn “Ibunt sancti” (The Saints Will Go Forth). Although discovered in a French manuscript, its musical structure is highly unusual and extremely rare in later Roman chant. Instead, it closely resembles the structure of modern pop songs, which is why it is considered evidence of Celtic chant.

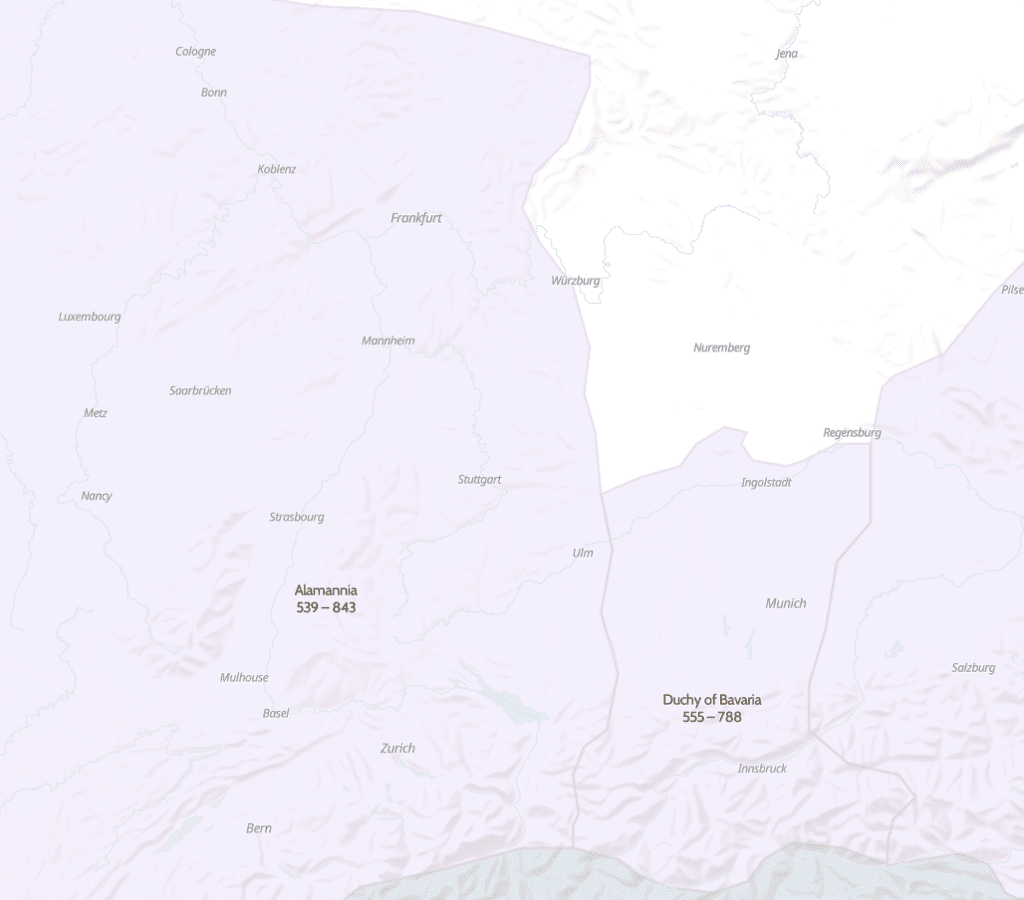

3、Gallican Chant

Gallican chant was the mainstream chant in what is now France. Its most distinctive feature was its “full-on dramatic flair”! Completely different from Rome’s minimalist style, the Gallic brothers sang chants as if performing in a play, complete with coloratura and even occasional improvised solos! The most audacious part was that they secretly incorporated Byzantine Greek lyrics and Eastern modes. However, this eclectic mix of sacred songs clearly didn’t sit well with the old Roman standard. With the rise of the Carolingian dynasty, Pepin the Short and Charlemagne, father and son, sought to align themselves with the Roman Pope, initiating a “de-Gallicization” movement. In 752 AD, Pope Stephen II personally visited the Frankish kingdom to demonstrate what “authentic Roman singing” was all about. This cultural superiority complex directly pushed Gallican chant to the brink of extinction. Charlemagne went even further, issuing a decree: Gallican chant was banned throughout the Frankish realm, and the official Roman version was to be used exclusively!

Although the Gallican Rite ostensibly disappeared, its musical DNA quietly seeped into the later Gregorian chant. According to historical records, the method of alternating between two tones in Gregorian chant is said to have been invented by the Gauls. Today, complete Gallican chant has been lost, and later generations can only attempt to reconstruct it through limited historical documents and artistic interpretation. For example, some tracks on the album *Sublime Chant: The Art of Gregorian, Ambrosian, and Gallican Chant*, released by “The Cathedral Singers, Richard Proulx (conductor),” strive to recapture the bold and unrestrained essence of Gallican chant.

4、Mozarabic Chant

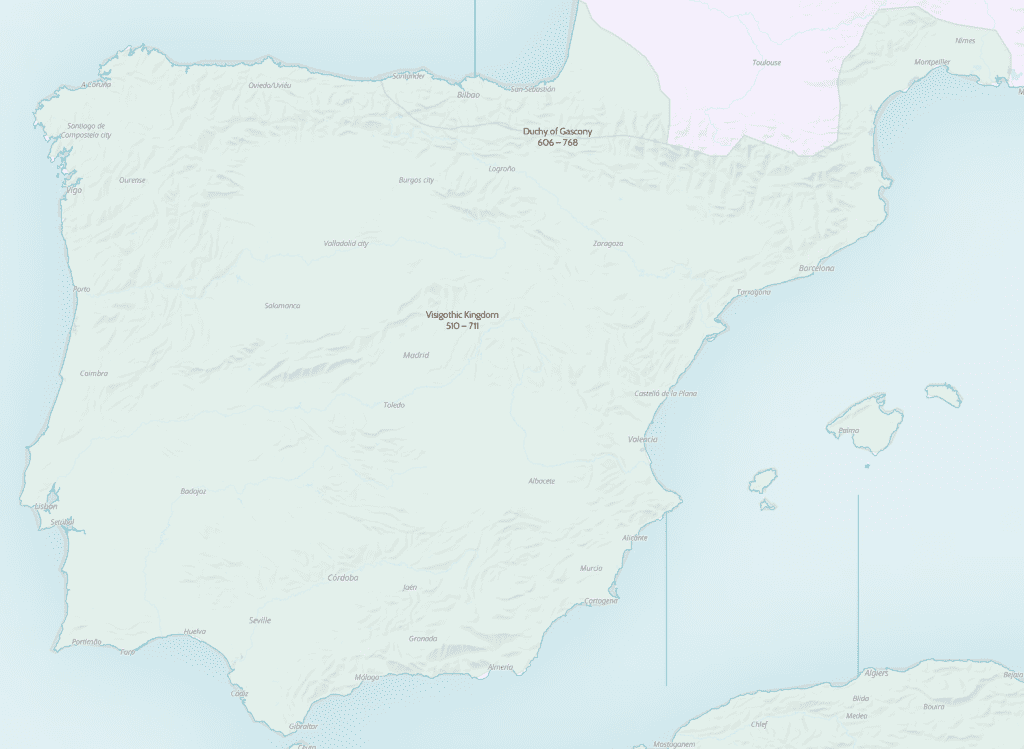

Before the Iberian Peninsula was covered by the Arab crescent moon flag, a unique chant had long echoed across this land—the Visigothic chant, later more commonly known as the Mozarabic chant. The name itself is a footnote to an era: “Mozarabic” derives from the Arabic “musta’rib,” meaning “Arabized,” referring to those Spanish believers who steadfastly held onto their Christian faith under Islamic rule. Yet, the roots of this chant run deep into even older soil; long before the Muslims crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in 711, it had already been the soul of the Catholic liturgy in the Visigothic Kingdom.

Its story is also an epic of faith, power, and survival. In 589 AD, when the Visigothic king declared in Toledo the abandonment of Arianism and conversion to Roman Catholicism, the Credo was already being sung in the liturgy of this land—a full four hundred years earlier than its use in Rome itself. This placed the Mozarabic rite closer to the Ambrosian and Gallican rites, forming a distinct tradition of its own, clearly separate from the later Roman rite.

The turning point came when the Christian kingdoms began the long “Reconquista” movement. In 1085, Toledo was recaptured and became the Roman Church’s stronghold in Iberia. The Pope appointed an abbot from the French Cluny Abbey as the Archbishop of Toledo, and Gregorian chant surged southward like a tide. Under the forceful promotion of Pope Gregory VII, the ancient Mozarabic chant nearly faced extinction—except for six privileged parishes within the city of Toledo, the traditional chants elsewhere gradually fell silent.

It should have vanished into history, yet it regained a faint glimmer due to one man’s persistence—in the early 16th century, Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros strove to revive this ancient tradition. He published the Missal and Breviary of the Mozarabic Rite and established a chapel within the Cathedral of Toledo specifically to preserve its liturgy. However, this revival was already a fusion incorporating Gregorian elements, and most of the pure Mozarabic chants from the Middle Ages had already faded away with the wind.

Today, we know very little about its true sound. Most of the surviving scores are written in neumes that are difficult to interpret, with only about twenty manuscripts preserving some translatable melodies. We only know that, like all plainchant, it is monophonic, unaccompanied male singing, which can be categorized into syllabic, neumatic, and melismatic styles. It possesses its own unique modal system, distinct from Gregory’s eight modes, and is closer to the freedom and regional character of Ambrosian chant.

The Mozarabic Chant can be said to be the most mysterious and fragmented branch of the European chant family. Born at the dawn of Christian Spain, it underwent acculturation during the Islamic period and ultimately retreated into a local relic amid the tide of Romanization. It was never fully assimilated, nor did it ever completely return. The songs preserved in the ancient churches of Toledo are thus not merely liturgical chants, but echoes of overlapping civilizations—an eternal memory of resistance and adaptation.

To this day, the Organum ensemble under the French label Harmonia Mundi and the monastic community of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, directed by Ismael Fernández de la Cuesta, have recorded Mozarabic chants that have been preserved and passed down. For example, the album “Mozarabic Chant” has effectively retained the essence of contemporary Mozarabic chant.

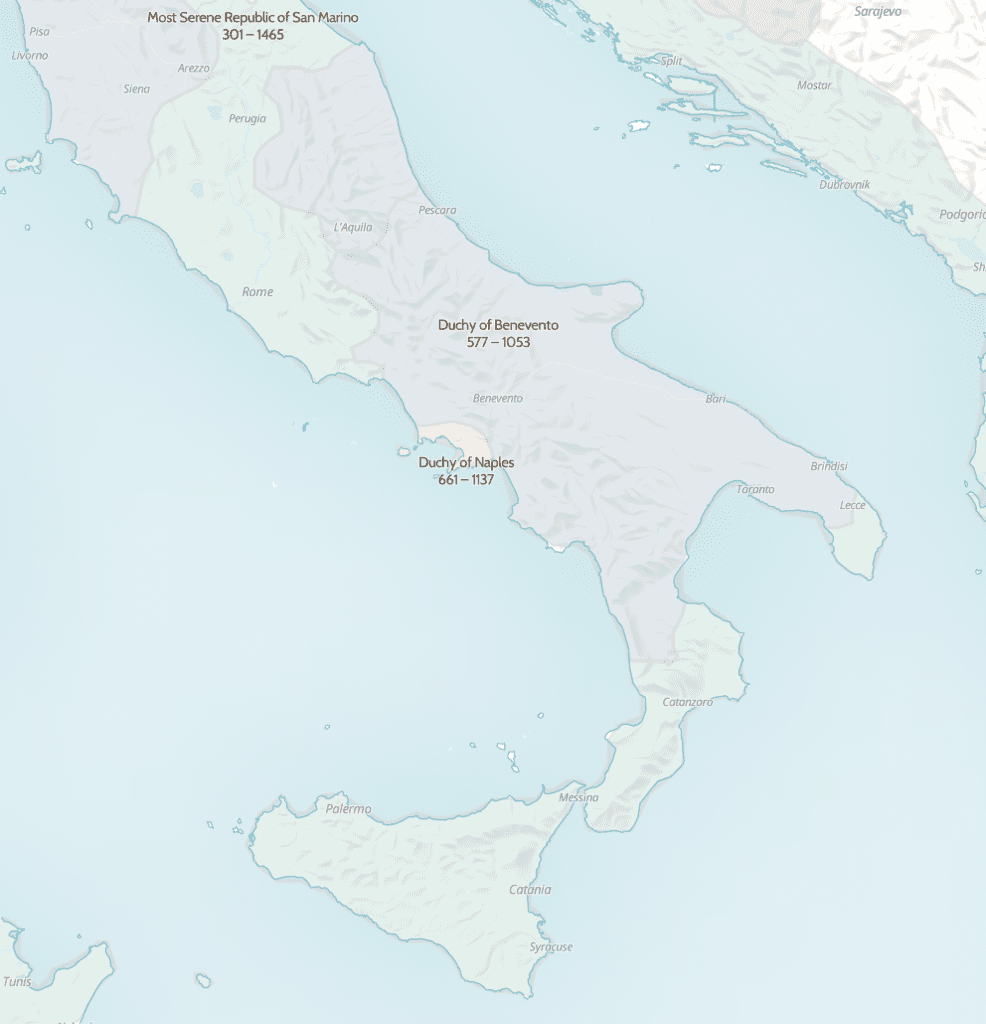

5、Beneventan chant

In the Duchy of Benevento in southern Italy, there once existed a unique and mysterious sound—the Beneventan Chant. It was an ancient, regionally distinctive liturgical music deeply rooted in Lombard culture. Today, it has almost completely vanished, surviving only like scattered pearls in a few 11th-century manuscripts, with the two most important Graduals preserved in the church library of Benevento.

These manuscripts themselves are like layers of overlapping pearls, precious and complex, documenting a musical world submerged by mainstream narratives. The melodic style of Beneventan chant is highly distinctive: it favors a narrow range, yet within these limited confines, it executes intricate and elaborate ornamental movements, making extensive use of repetitive short phrases, with an overall character that is ornate and introverted. This stands in stark contrast to the later Gregorian chant, characterized by clear structures and leaps of a fifth, and instead aligns more closely with another ancient tradition of Southern Italy—Old Roman chant.

Its demise is closely linked to the rise of a monastery—Monte Cassino. As the central stronghold of the Benedictine Order and a key promoter of Gregorian chant, Monte Cassino gradually conquered and assimilated the liturgical practices of the surrounding regions in the 11th century. Beneventan chant, much like Gallican or Mozarabic chant, ultimately could not resist the unifying tide of the Gregorian tradition and was gradually absorbed and replaced. Today, this chant has completely vanished into the annals of history, to the extent that most resources on chant make no mention of it. Yet, it stands as a testament to the diverse and regional expressions of piety that once existed in Southern Italy before the Roman standardized liturgy swept across Europe. Its fragmented remnants offer us a rare window into an alternative possibility of Christian music—one untouched by the shadow of Gregory the Great.

6、Ambrosian Chant

In 4th-century Milan, a bishop named Ambrose was quietly altering the historical trajectory of Western church music. At that time, Milan, as one of the ruling centers of the Western Roman Empire, stood at the crossroads of Eastern and Western cultures. Saint Ambrose introduced a novel style of singing from the Eastern Church—antiphons and responsorial psalmody—breaking the tradition of simple responsorial singing that had prevailed in the Western Church. More importantly, he personally composed hymns, integrating metrical poetry into the liturgy. Remarkably, the melodies of four of these hymns have endured for over 1,600 years and continue to resonate today.

Thus, Ambrosian chant was born. Yet it was not solely the creation of the saint; rather, it was a unique musical system that grew over centuries from the liturgical foundation he established. Unlike the later Gregorian chant, which unified the West, Ambrosian chant maintained its regional pride, with its liturgy bearing closer kinship to the Gallican and Mozarabic rites than to the Roman rite. Its melodies resemble a free-spirited poet, refusing to be confined within the eight-mode framework of Gregorian chant. Its most enchanting feature lies in the fluidity of its melodies—almost entirely eschewing leaps, relying solely on stepwise intervals to weave undulating, wave-like lines. The extensive use of a notational group called “climacus” reinforces this winding, forward-moving quality, lending it an ancient yet supple sound.

Its very survival is a story of resistance and miracle. After the 8th century AD, during the Carolingian dynasty’s push to unify Gregorian chant, ancient traditions such as Mozarabic, Gallican, and Celtic were gradually absorbed. Only Ambrosian chant stood firm in the city of Milan. Legend has it that to determine which liturgy was favored by God, the liturgical books of Gregory and Ambrose were placed simultaneously on the altar—both books opened on their own at the same time, as if divine will silently permitted the coexistence of both voices. Although it later inevitably came under the influence of Gregorian chant (especially in later additions to its repertoire), its core stubbornly retained its ancient character.

Even in 1622, attempts to forcibly fit its melodies into Gregory’s modal classification were widely considered to distort its essence. What truly kept its lifeblood flowing was its deep roots in daily liturgical life. From Matins to Vespers, the Psalms were chanted in a biweekly cycle, accompanied by brief and ancient antiphons. Its psalm tone system was complex and unique, with cadence formulas naturally guiding the singer back to the beginning of the chant. The chants in the Mass further highlighted its distinctiveness: there was no *Agnus Dei*, no *Ite, missa est*, and the *Kyrie* did not exist independently. Instead, it featured the *Fraction Anthem*, absent in other traditions, along with many *Transitorium* lyrics translated directly from Greek, quietly recounting its unbroken ties to the East.

Today, you can still hear it in the Archdiocese of Milan, parts of Lombardy, and Lugano, Switzerland. It was not swept away by the wave of liturgical reforms from the Second Vatican Council—in part, because Pope Paul VI was once the Archbishop of Milan. Thus, this strand of song, kindled since the time of Saint Ambrose, still flickers in ancient stone churches, like an unextinguished lamp, illuminating a musical path that has never been fully assimilated. Even now, you can visit the official website of the Milan Cathedral to experience the most authentic recordings of Ambrosian chant. As for the blog author, I recommend trying the album “Ambrosian Chant” performed by soprano Manuela Schenale. You can hear a splendor distinct from that of Rome, as if you could smell incense and Eastern spices.

7. Other Chants

There is very little textual reference for this part, such as in the regions inhabited by the Anglo-Saxons, where there should have been independently developed chants. These were significantly influenced by the Celtic Church, but very few materials have been passed down to later generations. The churches in these regions should have had their own development of chants throughout history, but over time, they were gradually incorporated and assimilated by Gregorian chant, lost to history.

Movement II: The Chosen Laborer – The Hardcore Life of Pope Gregory I

In the year 540 AD, Gregory was born into a prominent aristocratic family atop Rome’s Seven Hills. His father was a senator, and the family owned a mansion with gardens in Rome and a wine-producing estate in Sicily—equivalent to today’s top-tier elite who own a courtyard house within Beijing’s Second Ring Road and a vacation villa in Hainan.

Following the conventional script, Gregory should have spent his days wearing silk robes, riding in litters carried by slaves, and discussing with nobles in the Roman Forum topics like “how much tax should be levied this year” or “which province’s gladiators are more formidable.” In fact, he lived up to expectations, being elected Prefectus Urbi (Urban Prefect) of Rome at the age of 33—a position equivalent to today’s Mayor of Beijing, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and Commander of the Garrison, making it one of the most prestigious roles in the Roman Empire.

However, a family tragedy in 573 led this high achiever to question the meaning of life. After his father’s death, Gregory suddenly realized: What’s the point of being an official? What use is accumulating wealth? Witnessing the empire’s gradual decline, the Lombards’ menacing presence, and the rampant spread of plague, this wealthy man resolutely decided to give away his entire fortune, funding the construction of seven monasteries, and retreating into one of them as an ordinary monk. Some viewed this as a risk-avoidance strategy, but he firmly believed it was divine guidance.

Such a formidable figure naturally wouldn’t be content with a life of vegetarianism, prayer, and meditation. This former CEO brought corporate management into the monastery: he created a minute-by-minute daily schedule, developed an efficient assembly line for copying scriptures, and even reformed the monastery’s financial management system. The result was that, thanks to his superhuman abilities and financial power, his monastery quickly became the most efficient and well-stocked “model monastery” in all of Rome.

Pope Pelagius II soon recognized this talent. He first appointed him as ambassador to Constantinople (equivalent to a medieval version of an EU representative). During his tenure, he not only completed his diplomatic missions but also found time to engage in several rounds of theological debates with Eastern Roman theologians, emerging victorious each time.

In 589, Rome suffered a series of devastating blows: the Tiber River burst its banks, flooding half the city, followed by an outbreak of plague that claimed the life of the Pope himself. The Senate and clergy convened an emergency meeting, and to everyone’s surprise, they unanimously voted: “Let’s quickly invite Master Gregory to take charge!” This seemingly unbelievable outcome was actually because being Pope at the time was not a desirable position. Gregory was not so much inheriting the throne as he was being pushed forward to shoulder the blame.

It is said that Gregory was tending vegetables in the monastery at the time. Upon hearing the news, he wrote a resignation letter overnight and even attempted to hide in the forest to avoid the appointment—yet he was ultimately “captured” by the people and brought back to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, where he was forcibly crowned as the 64th Pope of the Catholic Church (serving from September 13, 590, to March 12, 604).

Upon assuming office, Gregory faced a hellish-level challenge: confronting the Lombard siege (military crisis), depleted granaries (economic crisis), ongoing plague (public health crisis), and church corruption (management crisis)—all problems of extreme difficulty. Yet, as a formidable figure destined for greatness, his actions became a textbook example of medieval crisis management. First, Gregory opened the church treasury to purchase grain and established a city-wide relief network. He then personally negotiated to repel the Lombards (legend has it he emerged from the city in white robes, intimidating the barbarians with his presence). Following this, he reformed church finances, establishing the first-ever parish budget system in history. Finally, he disciplined the clergy, dismissing bishops who were slacking off.

A seamless series of maneuvers, ultimately even exceeding the mission: he was going to reform the church music of the time—the chant! Gregory discovered that the chants sung in churches across different regions were all over the place—some sounded like Italian opera, some like Germanic war songs, and some even had a touch of Arabic flair. This CEO couldn’t stand it: “Is this acceptable? If the songs in every branch can’t be unified, how can the hearts of the people be united?” Thus, as the Pope who had already resolved a pile of messy affairs and whose prestige was soaring, he was about to personally kick off this music unification movement that would influence the next thousand years.

Movement III: Sacred Hymns and the Holy Dove – The Birth of Gregorian Chant

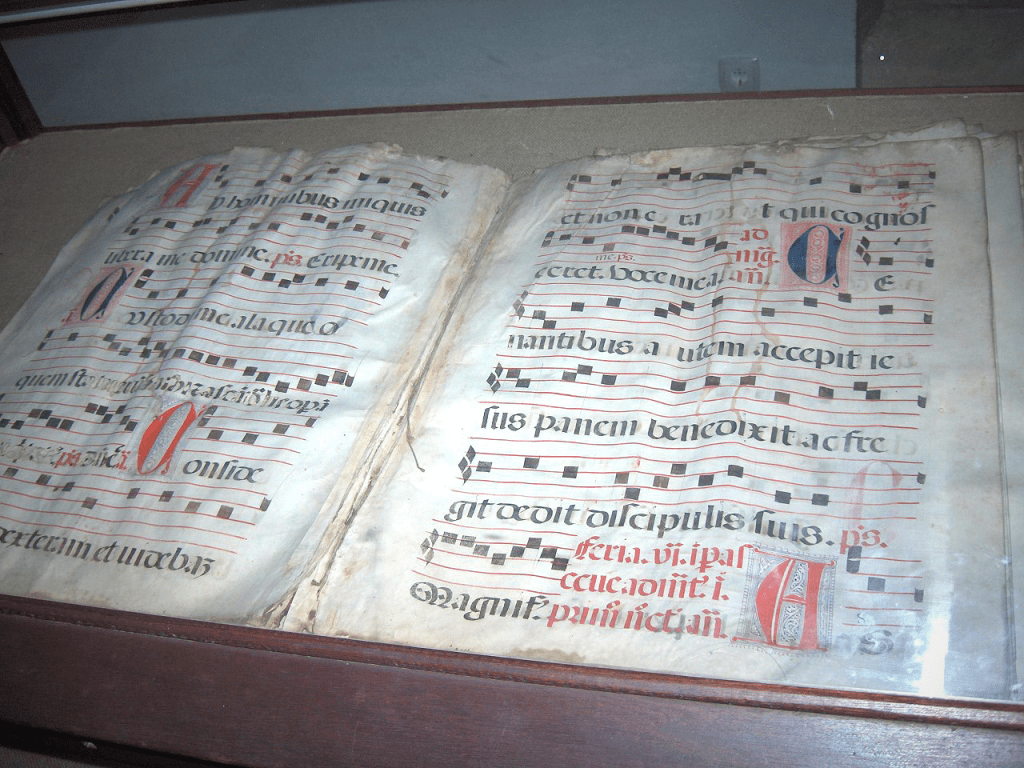

According to the official account passed down from the 9th century, one day while Gregory I was agonizing over the standardization of sacred chant, a dove embodying the Holy Spirit suddenly flew onto his shoulder and sang celestial melodies into his ear, phrase by phrase. The Pope hastily summoned his secretary to hide behind a curtain and transcribe the music in shorthand, thus creating the original notation of Gregorian Chant.

This legend sounds full of magical realism, but the medieval onlookers believed it—after all, how could a sacred dove have any ill intentions? It was far easier to accept than admitting that the sacred chants actually incorporated elements from Gaul, Rome, Byzantium, and even Arabia.

The actual process was far more mundane than the legend, yet far more intriguing. Gregory I was essentially a master of project management. His “Gregorian Chant Standardization Project” involved the following rigorous steps:

First, a team of monastic experts was established, dispatched with parchment to various regions to record local chant melodies. These expert teams were not just going through the motions—they needed to distinguish which were orthodox Roman chants, which were mixed with Gallic improvisations, and which carried an Arabic flavor. It must be said that these expert teams, personally appointed by the Pope, were indeed highly professional and quickly completed their first-phase mission.

Next, Gregory established a composition “office” in the Lateran Palace, with the Pope himself serving as the artistic director. The team included linguists to check Latin pronunciation, mathematicians to calculate interval ratios, and cantors responsible for trial singing and verification. After completing the standardization of Gregorian chant, the Pope once again dispatched expert teams to grassroots churches to promote the standardized Gregorian chant across various regions.

The promotion of Gregorian chant spanned several centuries, continuing even after Gregory’s own passing, as the Church and authorities vigorously promoted it as a tool of governance. However, the enduring legacy of Gregorian chant, lasting for a millennium, lies in its unique characteristics. First, it was performed exclusively with pure vocal tones, as the Church believed instruments would awaken carnal desires, and only the human voice could directly connect with God. In reality, this was to avoid the complications of disseminating music across churches with varying instruments. Next, it permitted only monophonic melodies, forbidding harmony—not because the Church was incapable of harmony, but to deliberately maintain a sacred and awe-inspiring tone, a principle later mastered by Apple. Finally, Gregorian chant had to be sung in Latin, regardless of whether one was Frankish or Saxon. This move single-handedly kept Latin alive for an extra five hundred years, until English ultimately unified Europe.

In any case, thanks to the efforts of the Pope, Gregorian chant was successfully promoted. In 604, this workaholic pontiff, despite suffering from a persistent fever, continued to dictate official letters. His final words were: “I have no more concern for anything in this world.” However, he probably never imagined that the Gregorian chant he had overseen and revised would continue to echo under the domes of every church in Europe for the next thousand years, becoming the most unique cultural IP of the Middle Ages and the most significant achievement of his life.

Movement IV: The Millennial Chant – The Development of Gregorian Chant

More than a hundred years after the death of Gregory I, Europe saw the rise of another formidable figure—Charlemagne, King of the Franks (April 2, 742–January 28, 814). When Charlemagne placed the jewel-encrusted crown upon his head in Aachen, this emperor, whose military prowess was unmatched, harbored an embarrassing secret: he was almost illiterate! Yet this did not hinder him from becoming a mastermind of cultural industry. Gazing at the vast empire stretching from the Pyrenees to the Elbe River on the map and listening to the clamor of dozens of dialects within his realm, Charlemagne slammed the table and declared, “We must find a cultural weapon to unify our thoughts!”

Soon this weapon was found—the Gregorian chant blessed by the Roman Pope. But a problem arose: the authentic Roman chant was slow and tedious, completely out of sync with the aesthetic tastes of the Frankish warriors. So, the court musicians of Charlemagne began their clever maneuver: they kept the lyrics of the Roman chant but secretly replaced the melody with a passionate, Gallic-flavored mode, as if setting Latin scripture to the background music of a Viking war song.

Charlemagne’s approach was remarkably forward-thinking and patient. In 785, at Charlemagne’s request, Pope Hadrian I sent a papal sacramentary containing Roman chants to the Carolingian court, mandating that every monastery in the empire establish a “chant training program” using the officially certified Roman *Antiphonale* as the unified textbook. Music instructors from Rome, funded by royal subsidies, traveled between monasteries to teach, while also discreetly checking for anyone secretly singing the old Gallic tunes.

To completely eliminate regional variations, Charlemagne’s engineers improved the musical notation system. They drew precise four-line staves on parchment, specified the duration for each neume, and even invented letter markings to indicate pitch. This system was so accurate that it allowed Saxon barbarians and Provençal poets to sing exactly the same melody—truly the earliest “music ISO standard” of the Middle Ages.

After thirty years of mandatory promotion, a miracle occurred: from Barcelona to Hamburg, from Brittany to Bohemia, the same melodic chant echoed from every church. Gregorian chant finally spread to broader horizons—Germanic warriors sang Latin with rugged voices, Italian priests added operatic vibrato, Celtic monks incorporated subtle ornamentation—yet the core melody remained consistent. This “standardization” unexpectedly fostered a grand musical fusion: the robust rhythms of the North met the ornate coloratura of the South, while the complex modes of Eastern Byzantium clashed with the simple cadences of Western Europe. It was precisely this hybrid quality that endowed Gregorian chant with greater vitality than its pure Roman original.

Modern musicologists have discovered through manuscript comparisons that the so-called “Gregorian Chant” promoted by Charlemagne actually incorporated numerous melodic characteristics of Gallican chant. For instance, certain passages of the *Introit* clearly carry the march-like rhythms of Frankish folk songs, while the *Offertory* conceals Celtic cyclical melodic patterns. Yet Charlemagne insisted on proclaiming this as “pure Roman tradition,” even commissioning the writing of the *Life of Gregory*, which detailed how the Pope was divinely inspired by the Holy Spirit to compose the chants. This marketing strategy was so successful that for eight centuries thereafter, people believed these melodies were truly written by Gregory I himself—proving that a good product needs a good story, and an even better product needs a fabricated one.

What Charlemagne never anticipated was that his forceful push for musical standardization inadvertently created the first “European cultural community.” When monks from various nations prayed with the same melodies, they unknowingly constructed a cultural identity that transcended national boundaries. This identity later gave rise to polyphonic music, propelled the Renaissance, and even laid the groundwork for the establishment of today’s European Union.

References for this article

This text is translated from the original Chinese version on the author’s blog. For quoted content, please refer to the original article.